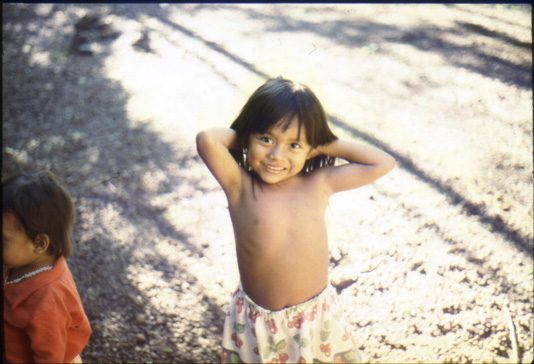

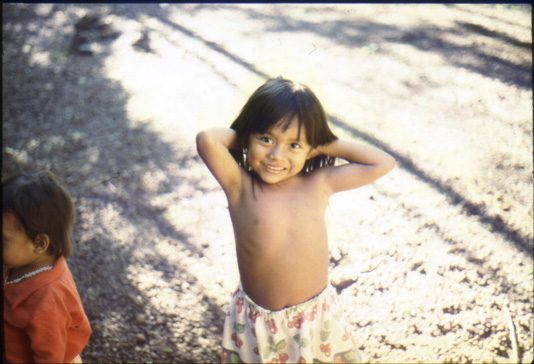

Piaroa children at play in San Juan de Manapiare.

Photo by Marisa Alcorta '99

STUDENT PERSPECTIVES

INCITO

by N. Salgado '99

Seemingly endless expanses of roadless areas, and rich diversity of human and non-human communities abound in the Amazon River basin of South America, challenging even the wildest of imaginations. However, in very recent evolutionary history of less than 500 years, unbridled development and climatic change, both anthropogenic in origin, have posed very real, serious threats to the integrity of the rare systems of Amazonas.

In the U.S. and abroad, when addressing human rights violations and environmental degradation, the two are often polarized, which is a handy tool for those perpetrating the violations. Instances of environmental injustice have not only displaced native cultures but also destroyed much of the integrity of the original ecosystems of North America and the rest of the world. Before we jump to the defense of "progress," we must take a hard look at the wake of this in light of the ruthless destruction of native ways and their supporting ecosystems and subsequent oppression of their values and legal rights in present society. One can consult a laundry list of dishonors since the arrival of European explorers - from ancient massacres at the hands of the conquistadores to the '49ers gold rush wiping out native Californian communities, to the Trail of Tears, to the farcical "sale" of Manhattan, to the more recent struggles of the Zapatistas, Cree, Haudenosaunee, Apache - the list goes on, to preserve what lands they have left and their lingering values. Ironically, as this ecocide occurs, researchers desperately seek out new tenets of what it means to live sustainably and technology attempts to offer life without expiration.

With the increasing pressure of free-market, global trade, and quelling debts, the great mining, oil, timber, and hydroelectric potential of the Amazon jungle has been an appealing canvas for high-level economic production for South American countries. From 1978 to the 1990's the square kilos of deforestation have increased exponentially, thanks to national policies supporting tax breaks for large corporations and ranches.

The reaction to these developments is not a clear-cut (no pun intended) case of foreign tree hugger sentiment. What is at stake is the several thousand-year-old legacy of an ecosystem at peace with its people - and vice versa.

Speaking at the first "international summit" of Indian tribes from Brazil, Venezuela and Guyana, Yanomami leaders said their lands and lives were being destroyed. "Our lands have been invaded by thousands of garimpeiros. At least 3,000 are illegally extracting gold on our lands," said Davi Kaponawa Yanomami. "They bring many diseases and death." The meeting in the capital of Roraima, was also called to discuss major international infrastructure projects, such as roads and power lines, that threaten indigenous territories in the three countries. The Yanomami Indian nation has appealed to the governments of Brazil and Venezuela to help expel thousands of the wildcat gold miners and clandestine logging firms from their Amazonian reserve. Tense standoffs between bow and arrow-bearing Indians and armed garimpeiros are frequent. In 1993, 16 Yanomami were massacred. Jose Siripino Yanomami said, "These garimpeiros are causing harm to our people and we want the governments to support the communities and the army which has to guard the border. If the garimpeiros were allowed in to cause damage, where would we hunt? If they contaminate the river, and poison the fish, what water will we drink?"

The nearly 100 indigenous leaders from Brazil, Venezuela and Guyana convened to protest and offer alternatives to development projects they claim are threatening the rain forest and their own livelihoods. Also topping the discussion agenda were logging projects, gold mining and superhigh- ways. The projects of most concern were: the proposed BR-174 superhighway that would cut from Manaus to Caracas; the 350-kilometer (220-mile) Georgetown-Brazil jungle road link; and Venezuela's mammoth Guri hydroelectric plant, with the potential to supply power to neighboring countries such as Guyana. During a larger summit in May, indigenous leaders from eight Amazon countries warned that such projects had already caused severe environmental damage to the region, including the pollution of prime fishing areas and the devastation of hunting grounds. "We demand land titles and demarcation before they proceed with any development projects," said Jose Poyo, president of the Venezuelan Indians Confederation, Conive. "We are not against progress," added APA's James. "But we must question who does it benefit? In most cases, not us. In fact our lives become even more miserable."

To the northwest in Bolivar State of Venezuela, the Warao, Kariña, Akawaio, and Pemon groups struggle against the potential destruction their communities face if the unchecked developments of the Imataca rainforest reserve continue. Three million hectares about the size of Holland will be allotted to mining and timber companies through the Decree 1850 Plan de Ordenamiento, which was approved by the Venezuelan president in May 1997 without any environmental or cultural impact statement or congressional consent. Ironically, this plan is stated by some officials to be a measure of protection against the wildcat destruction of the above "garimpeiro" types. Back in the U.S., Champion International is a timber corporation that has predominantly used lands in North America. They recently sold approximately 300,000 acres in the Northeast, leaving a swath of clear-cut land and economically depressed communities. Their new company plan? They have announced a new slashing of "non-strategic" plans, which involves shutting down most North American operations, which have been run pretty much dry, and "further developing South American prospects." This one case, not to mention hundreds of other American operations of this flavor, will have serious implications abroad for the jungle communities dependent on sustainable systems for milennia.

Fortunately, partnerships and organizations are springing up all over the world to support the people and native ecosystems of the Amazon as well the rest of the tropics. They range in scope from ethically concerned scientists who work to mitigate the impacts of their research, to the politically oriented, who drive for human rights, indigenous self-determination, and environmental protection clauses to be included in free trade agreements and corporate regulations, to ensure the integrity of all trading parties involved. New laws and suits are checking the unbridled development, but it remains to be seen if protection can move as fast as the land clearers. If you are interested, there are some local educational/activist groups dedicated to working on issues of this nature.

At Cornell you can get involved with CUSLAR (Committee on U.S. Latin American Relations), the American Indian Program, The Latin American Studies Program, the Greens, and others. Share your knowledge and with friends, family, public and our policy makers, an essential way to ensure that these ancient lands are here to stay--or they shall disappear unrecognized, like myths of old.